The five-year natural gas transit agreement between Russia and Ukraine is due to expire at the end of the year, halting around 13.7 billion cubic meters (Bcm) of supply the European Union (EU) would need to replace with additional Norwegian pipeline and LNG imports to meet current demand.

Prior to Russia invading Ukraine in 2022, Europe received nearly 150 Bcm of Russian pipeline gas through several transit points. But, as EU members moved to shrink reliance on Russian imports and sections of the Nord Stream system remained filled with seawater, pipeline shipments to Europe shrank to 14 Bcm last year. The majority of those remaining gas volumes were shipped through Ukraine’s pipeline network under the existing transit agreement.

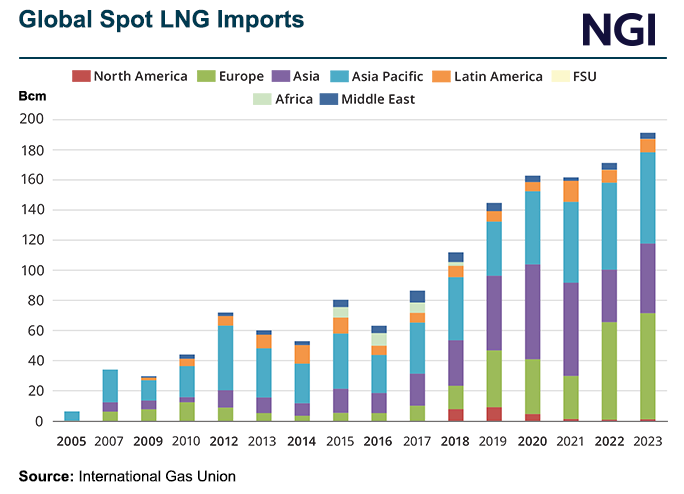

Rystad Energy Gas and LNG analyst Christoph Halser said without another third party to replace supplies shipped via Ukraine, “the EU will need about 7.2 Bcm of gas to be sourced from the liquified natural gas market.”

Although Russian gas giant Gazprom PJSC and EU countries most affected by the supply cutoff would like to continue with the transit contract, Ukrainian officials have cast doubt on a potential renewal of the agreement.

If the transit contract is not renewed, Russia would be left with one route to deliver gas to Europe. The Turkstream pipeline could turn Turkey into a Russian gas hub, connecting Eastern supplies to Bulgaria, Serbia and Hungary.

Jonathan Stern, a senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OEIS) told NGI, that European countries wouldn’t necessarily have a problem finding spare gas volumes to replace the additional lost supply from Russia.

However, the price and logistics of getting the gas where it needs to go is the real challenge.

“The problem is that the transportation costs those companies and countries will have to pay is significantly more – either from the south from Azerbaijan via the Trans Adriatic pipeline, Russian gas through the Turkstream pipeline or from the north with LNG imports via Germany, Lithuania, Poland and the Netherlands,” Stern said.

Austria, Moldova and Slovakia stand to lose the most of their current natural gas supply if Russian gas deliveries via Ukraine were halted. Austria and Slovakia count on Gazprom to deliver 8.9 Bcm of gas annually via Ukraine.

Akos Losz, a senior research associate at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, told NGI that Russia-dependant EU members would still have a few options left after the end of a transit agreement through Ukraine.

“Even in a full-stop scenario, the EU countries that still depend on the Ukrainian transit route would most likely be able to find alternative gas supplies and transit routes…,” Losz said.

Austria was the largest pipeline importer of Russian gas last year, and is looking to shore up energy security by importing more gas from Germany via the Oberkappel pipeline entry point. However, the pipeline’s capacity is not enough to meet Austria’s demand, according to calculations from Rystad Energy. Austria would likely have to import around 2.5 Bcm of gas via pipeline from Italy.

Italy is also expected to supply gas to Slovakia, and could potentially meet some of the demand with LNG imports via the Ravenna floating storage and regasification unit.

“With the Ukraine gas transit agreement due to end Dec. 31, the EU has been preparing for many months for this scenario…We have been working very closely with the member states, especially those most affected by this transit agreement, on their diversification options,” a European Commission spokesperson told NGI.

The EU is holding talks with Azerbaijan for a potential transit agreement to deliver gas to Europe using Ukraine’s pipeline network. Azerbaijan gas exports to Europe are forecast to reach nearly 13 Bcm by the end of the year, and the country is aiming to double exports to the bloc by 2027.

Under the EU’s Central and South Eastern Europe Energy Connectivity Initiative (CESEC), countries in southeastern and central Europe are working to create a new gas pipeline route, the Vertical Gas Corridor.

The corridor would use existing infrastructure in Ukraine and Moldova and enable LNG imports from Greece and Turkey to be delivered to Slovakia and Hungary. The system also would offer Azerbaijan a new route to deliver gas to east and central Europe.

Katja Yafimava, a senior OEIS research fellow, said she would not discount the possibility of a new transit arrangement being reached later in the year. Azerbaijan does not have sufficient gas to spare starting in 2025, she told NGI, an indication that a post-2024 transit question is an open one.